[translator's note] Kanzen shinsaku refers to the main games of a new Generation.

In the original interview, CGWorld abbreviates Scarlet and Violet as "S • V", using the uncommon middle dot.

Shun Onodera • Pokémon Character Modelling Lead

Suguru Fukaya • Pokémon Character Motion

Animation considerations based on the Ecology and Temperament of each Pokémon

[translator's note] Yoneya is the sub-manager of Creatures' art team under Fukaya, but is credited as the motion lead in Scarlet and Violet, which is a higher position than Fukaya's on those games.

[translator's note] San-men zu, literally "three-aspect figure", means views from the front, from above, to the side of an object.

[translator's note] Kyara uchi seems to be the shortened form of "character uchi-awase", literally "character meeting".

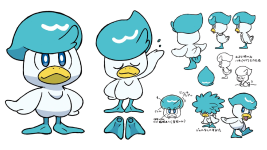

[bottom middle] Hair • Gel • The gel is bouncy • The same color as the body, but it has eyeballs (only on textures)

[bottom right] Non-gel form

[top right] It folds its wings (arms) only when swimming

Expressions:

[from left to right] Idle; Half-closed; Closed; Angry; Sad; Joyful; Damaged; Surprised

Collecting reference material, not only for living things, but also for inanimate objects

[translator's note] The "texture-based scroll animation" appears to refer to how all Pokémon games pre-Legends: Arceus had their eye textures on a single image, which would flip-between different points on the texture whenever an expression was called.

Rebuilding Texture-based facial expressions with joints

[translator's note] Sakuga hokai is a term that can refer to severely bad animation.

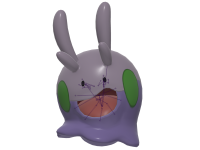

[right] Goomy's and Jigglypuff's facial expressions when taking damage.

The workflow of joint-based [animation] for facial assets is as follows, for each Pokémon:

- The animation team tells the modelling team what animation the Pokémon should have. Their ideas [must be] shared in detail: ex. whether [the animation] involves whole or partial body scaling; or whether [the Pokémon] also flails when opening its mouth wide.

- The animation team set up the joints and the [rigging] weight, using this shared information. They then set the Root Joints, which allow the entire eye to move as parent nodes, and configure [each child node] for the intended facial expressions and shape, depending on each Pokémon.

- As for older Pokémon, the motion team tries using the existing facial asset data, checks for errors or clipping glitches, and debugs them.

- The final assets for the facial expressions are formed into a preset and registered to their in-house tool.

[translator's note] The "surface patterns" appear to refer to the normal maps that allow for a degree of texture on a Pokémon's body in Scarlet and Violet, such as Seviper's scales.

[translator's note] A "symbol encounter (shinboru enkaunto)" is a wasei-eigo that refers to a fully visible encounter, either spawning or stationary.

Additionally— Fukuya's use of "the 30 FPS era" is vague. It wouldn't make sense for him to be referring to their development setup, as ever since the debut of these models in Pokémon X and Y, the Pokémon have been animated at 60 FPS, albeit this can only be seen exclusively in specific menus within the Generation 6 games.

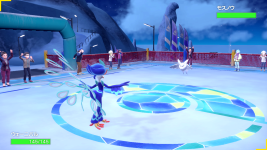

[right] Scarlet and Violet requires transitions between idling and running in the open world, which has changed Passimian's animation so that it now runs with the berry held in its hand.

Meticulously developed post-attack animation featuring weight transfer

[translator's note] Weight transfer is an athletic technique of shifting body weight from one part of the body to another during action. In-game motion for that is a level of animation follow-through after a Pokémon makes a sharp move, which makes it look more natural.

The first is a balance with the time scale [of the attack]. An attacking animation [has to] have quite a short duration between its launch and the [final] hit, so there's only so much you can portray. [Our rules] are, therefore, that the animation before the hit should emphasize the coolness of the movement, and the one after the hit, which is the longer [part], should be crafted with great[er] attention to detail.

The second is how to transition back to the idle animation. [To make this transition more seamless,] we've adjusted the animation curve, overall movement flow, etc. so that the gap between attacking and idling doesn't stand out.[translator's note] There was a misprint on the printed version where the highlight for the interviewer's text was missing.

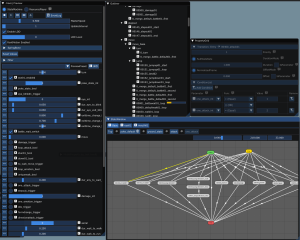

[right] Screenshot of a dedicated tool for the workflow of animation-state transition adjustments.

[translator's note] The tool appears to be fully in English, with the only exception being "保存" the Save button.

Some animators challenge themselves with animation they consider themselves weak at

[translator's note] The staff appear to use the word "gimmick" to describe an appendage or an otherwise unique aspect of that Pokémon's design. This is different to the technical term of “shader gimmick” that is used elsewhere in the article.

Portraying life-likeness despite various limitations

[right] Chi-Yu's happy animation, where its eyes are wide open and only its magatamas shine.

[translator's note] A "range of interference" of an object appears to refer to the space occupied by the object that disallows clipping.

[second] Varoom is based on a single-cylinder engine, which caused difficulties when discussing how it should be interpreted in motion.

[third] Roaring Moon has long front legs and claws, and short back legs, which makes it prone to clipping during development of its walking animation, among others.

Developing animation not only on land, but also in air and water

Creatures, Inc.'s Role: Expanding how Pokémon are expressed

[translator's note] Wakasugi appears to have comparisons with 3D animation films in mind.